(Asian independent) Two Indians engaged in the Second Boer War (1899-1902) in South Africa, which is known in history books as the ‘dirty war’, were to leave behind their imprint on their mother country’s history.

Their paths may not have crossed in the course of the war, which was being covered, incidentally, by a reporter for the ‘Morning Post’ named Winston Churchill, who was to become very important for India later, but when the two Indians met finally in 1921, they gave birth to the Tricolour, which is being celebrated in a massive way by the Har Ghar Tiranga campaign this Independence Day.

One of the Indians was Sergeant Major Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, leader of the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps, who hoped, mistakenly, to gain British sympathy for Indians living in South Africa, because of the stellar work done by his band of stretcher bearers. It got him the Kaiser-i-Hind medal — and little else.

The other was young Pingali Venkayya, a British Indian Army soldier despatched to South Africa to fight in the war. It was in South Africa that the young man was struck by the sense of nationhood the Union Jack inspired among British soldiers. He may have been young, but he recognised the ceremonial importance and binding power of a national flag.

The morning and evening flag rituals of the British Indian Army stayed in his mind and upon his return to India, he dedicated many years to designing a flag that represented the country’s ethos and national aspirations.

The credit for unfurling the first Indian national flag in Stuttgart, Germany, on August 22, 1907, goes to Bhikaiji Cama, a globe-trotting nationalist from Bombay, but it was Venkayya’s design that inspired the Congress flag during the freedom struggle, and thereafter, the Tricolour.

Venkayya was born on August 2,1876, at Bhatlapenumarru, close to present-day Machilipatnam town in Andhra Pradesh. He was a farmer, a geologist, a lecturer at the Andhra National College in Machilipatnam, and fluent in Japanese — so fluent that he first attracted attention when he was able to deliver a full-length lecture in that language at a school in Bapatla, a town in Andhra Pradesh, in 1913. He became instantly famous as ‘Japan Venkayya’.

He was also known as Patti Venkayya because of his research into the Cambodia Cotton. Patti means ‘cotton’, which was very important for Machilipatnam, a former port city that became famous for its Kalamkari handloom weaves.

Despite these diversions, Venkayya did not lose sight of his ambition to design a national flag for India. In 1916, he published a booklet titled ‘A National Flag for India’. It not only surveyed the flags of other nations, but also offered 30-odd designs of what could develop into the Indian flag.

That was all very good, but he had to catch the attention of someone prominent and sell his design for a national flag. He decided to catch up with Gandhi, about whom he evidently knew from his days in South Africa, but he could not, although he tried to catch his eye in the Congress sessions held between 1918 and 1921.

Finally, the big opportunity came at an extraordinary session of the All India Congress Committee on March 31 and April 1, 1921, in Bezawada (today’s Vijayawada, the second biggest city of Andhra Pradesh), where the Congress was meeting to accept the overarching leadership of Mahatma Gandhi.

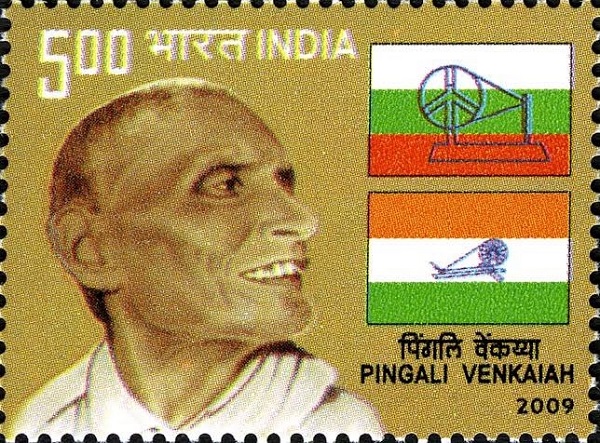

On March 31, Gandhi spared some time for Venkayya, who presented his version of the national flag to the Mahatma — it consisted of two stripes (green and red) and the Gandhian charkha at the centre (from left to right). On Gandhi’s suggestion, Venkayya added a white stripe on top, and this was the original Tricolour.

The design obviously struck a chord with Gandhi because he called Venkayya for another meeting the next day, but his preoccupation with the Congress Working Committee kept him away. He acknowledged this meeting in an editorial in his newspaper, ‘Young India’, where he explained that the red band symbolised the Hindus and the green, the Muslims.

It was very different from the flag unfurled by Bhikaiji Cama in Stuttgart, which was green (representing Muslims, oddly with a row of lotuses running across the band), yellow (for the Buddhists, with Vande Mataram inscribed in Devanagari script) and red (for the Hindus, with a crescent-shaped moon and the sun on two corners of this band).

It must have been the simplicity of Venkayya’s design and the primacy it gave to the charkha, the symbol of the spirit of Swaraj, that appealed to Gandhi, who spoke at the Bezawada session in favour of the idea of having a national flag ready.

Venkayya’s flag was used informally at all Congress meetings since 1921, but it was not until its 1931 session that the Congress adopted the Tricolour with the colour scheme we have grown up with — saffron, white and green — and the charkha at the centre.

It became the standard of the freedom movement that the Mahatma’s non-violent soldiers carried with pride and hoisted on their home and shops, braving police lathis and imprisonment.

Venkayya died in penury and oblivion in 1963, only to be retrieved from the footnotes of history much later. A postage stamp in his honour was released in 2009; the Vijayawada station of the All India Radio was named after him in 2014. And last year, his name was proposed for the Bharat Ratna by Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister, Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy.

In his lifetime, Venkayya never sought state honours or any compensation for his contribution to designing an essential part of our national identity.

His greatest reward was the fruition of the seed of an idea that had been planted in his formative mind during the Second Boer War.