(Kanwal Bharti)

(English translation from original Hindi by S R Darapuri I.P.S.(Retd)

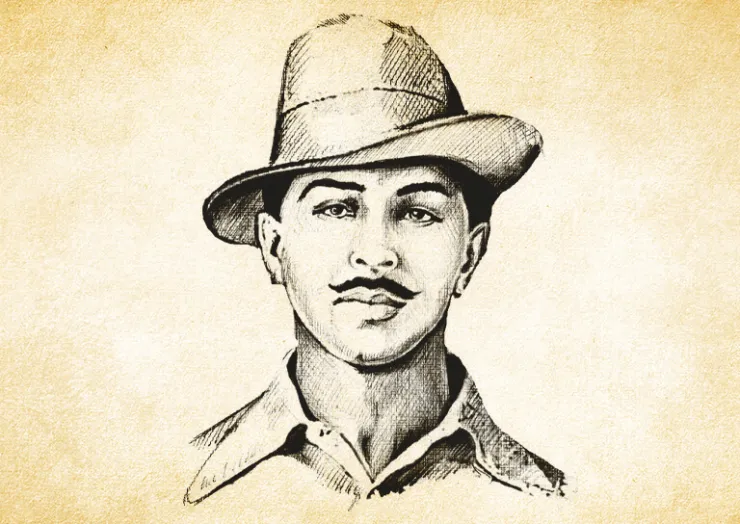

(Asian independent) For a long time, I wanted to think about Bhagat Singh’s (1907-1931) patriotism, revolution, and ideology from a Dalit perspective. I had also written a couple of small comments on Facebook, which were not liked by most intellectuals. Bhagat Singh has become synonymous with revolution in our country. He is accepted in all camps, whether leftist or rightist. Therefore, criticizing him is a big risk, no doubt about it. But it is also not right to suppress expression out of fear of the dangers of risk.

The basis of my evaluation is mainly two books, one is “Bhagat Singh and his comrades’ documents” edited by Jagmohan Singh and Chaman Lal, published by Rajkamal Prakashan, New Delhi and the other is “Bhagat Singh and his comrades’ complete available documents” edited by Satyam, published by Rahul Foundation, Lucknow. Although there are some other books as well, such as Yashpal’s ‘Singhavalokshan’, Shiv Verma’s ‘Samritiyaan’ and Manmathnath Gupta’s ‘Indian Revolutionary Movement Ka Itihas’. There are some books by Sudhir Vidyarthi as well. But I have not used these books in my evaluation.

In my view, the countrywide protest against the Simon Commission by the Congress, the killing of Saunders by Bhagat Singh in reaction to Lalaji’s death due to police lathicharge during Lala Lajpat Rai’s demonstration in Lahore are some of the subjects on which I can never agree with Bhagat Singh’s actions. Looting government treasury from a train, committing murders and exploding a bomb in the Parliament are also not revolution in my view. Although I agree that revolution cannot happen without violence, and that killing someone in a revolution is also possible, but my question is whose murder? What revolution happened by killing an English officer? Why was the treasury looted from a train? Will robbery be called a revolution? If dacoity is revolution, then why should Sultana dacoit not be called a bigger revolutionary than Bhagat Singh and his comrades, who used to loot the wealth of the rich and donate it to the poor, and get poor girls married? It is understandable that money is needed to buy weapons. But it is not understandable to loot the government treasury for this. They could have looted any landlord or businessman, who were the biggest exploiters of the people even during the British rule. They used to eat and drink lavishly even during epidemics like famine. Why did the weapons of Bhagat Singh and his comrades not turn towards those landlords and businessmen?

There is no doubt that Bhagat Singh’s thoughts were revolutionary. But he got very little life. He became a martyr at the age of just 24 years. If we exclude a few years of early upbringing and education, then the age of twelve-thirteen years cannot be said to be enough in terms of maturity. Although he was among those exceptions, who were ideologically mature even at such a young age. But that age is also emotional. The kind of patriotism that he displayed was nothing but his mere sentimentality, which does not match his ideology.

Bhagat Singh and his comrades come to light with the murder of Saunders. The period of 1928 is at the root of this entire episode. And this story begins with the arrival of Simon Commission in India and its nationwide protest by Congress and Hindu Mahasabha. I will discuss why Simon Commission was opposed and boycotted sometime later. For now, let us discuss this incident that when Simon Commission went to Lahore, Lala ji was injured in the lathi-charge of police in the protest led by Lala Lajpat Rai, and due to that he died. Historians have written different dates of Simon Commission’s visit to Lahore. According to Sumit Sarkar, this date is 30 October, whereas Manmathnath Gupta has written this date as 20 October. Lala ji died on 17 November 1928, so this date should be 20 October only. According to Jagmohan Singh and Chaman Lal, ‘Despite not having a very good opinion about Lala Lajpat Rai, the revolutionaries considered Lalaji’s death a national insult and avenged it by killing police officer Sanders who had beaten Lalaji with sticks.’ Two notices were duly issued on 18 and 23 December 1928 under the signature of Balraj, Commander-in-Chief of the Hindustani Socialist Democratic Army, stating that this was the biggest insult to the nationalism of this country and now it has been avenged. If our enemies help the police in revealing our whereabouts, strict action will be taken against them. It was also written in the notice of 18 December, ‘Bureaucracy beware! Oppressive government beware! Do not hurt the sentiments of the Dalit and oppressed people of this country. Stop your evil acts. Despite all your laws and vigilance made to prevent us from keeping weapons, pistols and revolvers will keep coming into the hands of the people of this country. Even if those weapons are not sufficient for armed revolution, they will be enough to take revenge for national insult. No matter how much the foreign government oppresses us, we will always be ready to protect national honour and teach a lesson to foreign atrocities. We will keep the call of revolution high despite all opposition and oppression and will shout even from the gallows – Inquilab Zindabad! We regret killing a man. But that man was a part of that cruel, vile and unjust system, which must be abolished. This man has been murdered as an agent of the British rule in India. This government is the most tyrannical government in the world. We regret shedding human blood. But sometimes it becomes necessary to shed blood on the altar of revolution. Our aim is a revolution that will put an end to exploitation of man by man.’

In this notice, the Dalit and oppressed people have been needlessly defamed, whereas the poor Dalits had nothing to do with Lala ji’s demonstration against the Simon Commission. Some foolish Dalits must have been gathered in the form of a crowd. That entire demonstration was to save Hindus’ face. Hindus were opposing the Simon Commission so that it could not know anything about the socio-economic and political condition of the Dalit classes of India and their demands. It is true that there was no Indian member in the Simon Commission. If there was, it would have been a Brahmin. And Brahmins do not have a judicial character, this was known to the British as well as the people of the Dalit class.

Anyway, coming to the point, Hindustan Samajwadi Democratic Army has justified the shedding of blood to take revenge for national insult in its notice. Taking revenge is not a good strategy of any movement, it is madness. I wish the Dalits had also taken up arms and avenged their atrocities by shedding the blood of the Brahmins and Thakurs! Because these were the people who had kept a large population of India poor and miserable by depriving them of wealth and education. These were the most exploitative and tyrannical people of India. The British government was not the most tyrannical government in the world, but the most cruel and tyrannical people in the world were the Brahmins and Thakurs. If an armed revolutionary group had emerged among the Dalits like Bhagat Singh in that era and had massacred a thousand or two thousand tyrannical Brahmins and Thakurs, then the fortunes of the Dalits would have changed. But the Dalits did not believe in violence. They were democrats. Ambedkar also never inspired the Dalits to take up arms and commit violence; because he knew that the caste system and the alliance of Brahmins, Thakurs and Baniyas who were made rulers in it had not left the Dalits in a situation where they could take up arms. He never used the plough, which he used to plough their fields every day, as a weapon against the Brahmins and Thakurs.

Did Bhagat Singh not realize that the atrocities committed by the British on Indians were not as barbaric as the atrocities committed by the Brahmins and Thakurs on the Dalit castes? The atrocities committed by the British government were the actions of law and order, which have not decreased even after the British left. Which government does not suppress violent protests against the government? Did the Congress governments not suppress the public resistance? Is the BJP government of today not suppressing the public resistance? But the atrocities committed by the Brahmins and Thakurs on the Dalits were not the suppression of any resistance, but were deliberate conspiratorial atrocities to keep them suppressed. Did Bhagat Singh not see the news of barbaric atrocities on the Dalits, which were published in the newspapers of his time? Did he not see atrocities being committed on the Dalits in Punjab? Then why was he not disturbed by them? Weren’t they a matter of national humiliation for him? If not, then why were they not?

Bhagat Singh must have read Katherine Mayo’s book ‘Mother India’, in response to which Lala Lajpat Rai wrote the book ‘Unhappy India’. Mayo has written in ‘Mother India’ that the Dalits of entire India, who were called untouchables in those times, were grateful to the British government, due to which they got civil rights for the first time in India. Ambedkar also called the British government a boon for the Dalit classes, whereas the Hindu ruling class had been a curse for them for centuries. Bhagat Singh’s devotees may be offended by the name of Ambedkar, and can make this allegation, in fact they have also been saying that Ambedkar was a devotee of the British government. But this does not make any difference to the truth. Mayo has written that in 1917, the untouchables in Madras Presidency, while opposing Swaraj, had appealed to the government to ‘save them from the Brahmins, whose aim is to gain control over the government in the same way as a wheat-bearing snake wants control over frogs.’ Madras Adi Dravida Jan Sabha, an organization of 60 lakh tribes of the same presidency, had said that ‘We are strongly opposed to Swaraj. We will fight till the last drop of our blood against the British attempt to hand over the power of India to the Hindus. The laws of the British are our protectors.’ The Dalit class of India wanted to keep the British government in India, because the British had opened the doors of their liberation. Bhagat Singh wanted freedom from the British, but he did not pay attention to the untouchables, who were kept as slaves by the Hindus. India was under the British, but the Brahmins and Thakurs of India were not slaves. They lived in complete freedom and feudal splendour. Katherine Mayo, in her second book ‘Slaves of the Gods’, has mentioned Banerjee, a social reformer of Bengal, whose drawing room was decorated with precious foreign furniture, crockery and other rare items, and his wife had returned from England. But on the other side of their luxurious splendour, right in front of them was a slum of poor people, miserable and deprived.

Now let us come to the murder of Saunders, which was committed by Bhagat Singh. Two things have been said in this matter, which need to be considered. One is that the revolutionaries did not have a very good opinion about Lala Lajpat Rai, and the second is that Lalaji’s death was the biggest insult to the country’s nationalism. Regarding the second thing, we can believe that despite differences in opinion with Lalaji, there was sympathy for him on humanitarian grounds, because he was a great leader of the nation, so his death was a loss to the nationalism. But how can it be called an insult to nationalism? Was Lalaji the only one to face the lathi charge in that crowd? Did Bhagat Singh ever think that if the power of the country had come into the hands of Lala Lajpat Rai, what kind of nation would he have built and what nationalism would he have respected?

Let us come to the first thing. The revolutionaries did not have a very good opinion about Lala Lajpat Rai, but what was that opinion? It is important to know this. We present it here from the documents of Bhagat Singh and his comrades. According to Satyam, an open letter addressed to Lala Lajpat Rai was published in November 1927 in the Lahore-published ‘Kirti’ magazine. After that, an article titled ‘Lala Lajpat Rai and Miss Smedley’ was published in January 1928 and another article titled ‘Lala Lajpat Rai and the Youth Movement’ was published in August 1928. An editorial comment was also published in ‘Kirti’ on 18 September 1927. In this comment, it was said, “The gentlemen who have had a good deal of dealing with Lala Lajpat Rai in political life, know very well Lalaji’s mere desire for leadership and that he does nothing for the country except blabbering. Brothers living abroad, especially Sikhs residing in America, lost faith in Lalaji in 1914 itself, when he went to Canada and America and those Indian brothers gave him a lot of their hard-earned money for the cause of freedom in India, and according to those brothers, Lalaji spent that money as per his wish and usurped a lot of money himself. “

After this editorial comment, let us now take that open letter, which has the signatures of 22 people. In this letter, they had made five allegations against Lala Lajpat Rai: political indecisiveness, betrayal of national education, betrayal of Swaraj Party, increasing Hindu-Muslim tension, and becoming a liberal. It is written in this letter, ‘Other gentlemen like you had propagated ‘Kill the Muslims.’ When the time came for Muslims to be killed, their leaders showed this weakness and they could not act like soldiers. In this way, they also suffered a lot. But our soldier proved to be a brave man in showing cowardice at that time. When Hindus started getting killed, you thought it better to go to Europe sitting on first class mattresses. Referring to the people killed in the riots, it is written in the letter, ‘Many young women lost their husbands and their whole life was full of sorrow and loneliness. Many virgin girls are crying with tears within themselves due to the violation of their chastity. Many innocent people were killed. 30 lakh lives are going through a terrible hell. The Governor of Punjab leaves his hilly resting place and comes to Lahore to cut the thorns sown by these people, but our soldier Lala Lajpat Rai is so ill that he cannot reach his duty and says that it is very hot in Lahore and the railway seats have already been booked. Let these widowed women cry, orphaned children, what do we have to do with them. Troubles bring strange people together.’ In an article titled ‘Lala Lajpat Rai and Agnes Smedley’, written either by Bhagat Singh or his associate (because neither Satyam nor Jagmohan Singh and Chaman Lal could find out the real author), it is stated that Lalaji had stopped publishing Agnes Smedley’s articles in his paper ‘The People’ because he no longer liked Smedley’s ideas and found them smelling of Bolshevikism. The article further states, ‘Lala Lajpat Rai is a staunch supporter of the workers. He has also been the President of the Trade Union Congress. He attended the International Labour Congress in Geneva as a representative of the workers. You used to write to Mr. MacDonald and Company as capitalists and supporters of dictatorship. But who are you? A worker? No, not at all. You are a real capitalist and are friends with the capitalists. You had gone to Geneva with Mr Birla on the pretext of your health and had been helping him there.’

The article further says, ‘Lalaji, you are omniscient. In front of you, illiterate Sikh brothers came here in groups from America and appealed to the people not to help in the war. Now is the time, the iron is hot, strike a strong blow and become free. No one listened to them. But they fulfilled their duty by attaining martyrdom. At that time, you knew everything. It was nothing new for you. Had the truth within you died? (Did) you yearn to return to India? You wanted to come to India as a good person in the eyes of the British, so you remained calm and remained silent. To be loyal to the British, you kept writing against the Germans. Why, Lalaji, is that right?’

There is more in the article. For example, ‘Is communism not sectarianism, at least in today’s world? Is it not an organised struggle of one class against another? Lalaji says this. But Lalaji, please tell us yourself whether you have come to communism thinking it to be a sectarianism? You must have thought, why become a communist, people become Hindus after all.’

At the end of the article it is said, ‘If truth be told, ‘Punjab Kesari’ has become old now. Now it has become ineffective like a pet lion of the circus. Some poet has rightly said, the sky changes its colour in so many ways.’

In the second article ‘Lala Lajpat Rai and the youth’, Lalaji’s views towards the youth have been criticized. These youth were none other than revolutionaries like Bhagat Singh, whom Lalaji had criticized. In the second paragraph of the article it is written, in the last council elections, Lalaji left the Congress and started opposing it and during this time he kept saying such things, which did not suit him in any way. Seeing this, some sensitive youth raised their voice against you. To take revenge for that, Lalaji openly said in his speeches, that these youth are very dangerous and pro-revolution and want a leader like Lenin. Also, he said that if these youngsters get a job of even Rs. 50, they will sit down like foam. What does this mean? Were the youngsters who gave up their ideals for Rs. 50 with Lenin? Is Lenin of the same level? If not, why was such a thing said? Just because Lalaji, on the one hand, is inciting the government to take strict action against them, on the other hand, he is also trying to lower the respect of the youngsters in the eyes of the public.’

The article further quotes an article by Lalaji, in which the youngsters have also been opposed. ‘Lalaji says that the public should avoid the speeches of the youngsters of today with radical ideas. They are supporters of the revolutionary’s revolution. Their propaganda for property is harmful, because there is a fear of class-struggle breaking out due to this. This work has been started at the instigation of some foreign elements. Those external elements want to create a rift in our national movement, so it is very dangerous.’

Opposing Lalaji’s views, the article further states, ‘First of all we want to tell that no foreigner is misleading us for this propaganda. The youth are not saying such things under someone’s instigation, but now they have started feeling it from within the country itself. Lalaji himself is a big man, he travels in first or second class. How does he know who is travelling in third class? How does he know who has to face kicks in third class passengers? He passes through thousands of villages sitting in a car with his friends, laughing and playing. How does he know what thousands of people are going through? Today, does the writer of a book like ‘Unhappy India’, seeing the crores of people in Hindustan, who cannot even fill their stomachs after toiling hard from morning to evening, still need someone from outside to come and tell us to find a way to fill their stomachs. We see farmers working day and night in the heat, cold, rain, sunshine, hot winds, and fog in the villages. But those poor souls are surviving on dry bread and are burdened with debt. Even then, don’t we feel aggrieved? At that time, don’t our hearts rage? Even then, do we need someone to come and tell us to try to change this system? When we see every day that workers are dying of hunger and those who sit idle and eat are enjoying themselves, can’t we feel the problems of this economic and social system?’

Further in the article, while feeling the condition of the untouchables, it is said, ‘Don’t we feel angry seeing the painful conditions of millions of people whom we have kept away by calling them untouchables? (These) millions of people can develop the world a lot, they could have served the people, but today they seem like a burden on us. Is there no need for a movement to improve their condition, to make them fully human and to just get them above the well? Was it not necessary to bring them to such a state that they can earn and live like us? Is a revolution in social and economic rules not necessary for this?’

Further he accepted that the Russian Revolution has changed him. For example, ‘We believe that the things whose solution we cannot think of ourselves right now, the Russian scholars, while suffering throughout their lives, while ending their lives bit by bit, have put their views before the world. Should we not get the benefit of that? Is it Lalaji’s intention that now a revolution should be done against the British rule and the reins of the rule should be given in the hands of the rich? Crores of people should fall into not just this but even worse conditions and die and then after hundreds of years of bloodshed, we should again come on this path that we should do a revolution against our capitalists? This would be stupidity of the highest order.’

Further, the article mentions an important point which Dr. Ambedkar had also told the communists and which the communists had ignored. For example, ‘Lalaji does not have time to go to the villages. How would he know what the people think? People clearly say that what is the benefit of revolution to us? When we have to work hard to earn our daily bread, and even then, the Nambardar, Tehsildar and Thanedar have to commit atrocities in the same way and collect rents in the same way, then why should we lose our present bread? Well, suppose there is a revolution here, then according to Lalaji, who will be given the rule? Will it be to Maharaja Vardhaman or Maharaja Patiala and the group of capitalists?’

These thoughts prove Bhagat Singh and his comrades to be the most ardent socialist thinkers of that era. But they sacrificed their lives for an anti-socialist, extreme capitalist and Hindu leader Lala Lajpat Rai, who, if alive today, would certainly have been a leader of the RSS and BJP. What revolution did Bhagat Singh and his comrades bring about by sacrificing their lives for such an anti-revolution leader? Were they born to sacrifice their lives for Lalaji, or to give the country a socialist system? By being hanged for emotional nationalism, did they not end their entire movement for revolution along with their bodies? Did the movement of their Naujawan Sabha move forward after their martyrdom? Youths like Chandrashekhar Azad, who displayed his sacred thread, and Ashfaq, Bismil, Sukhdev, Rajguru were only victims of emotional nationalism. They were not intellectuals like Bhagat Singh, they were just emotional patriots. But, if he had not been caught in emotional nationalism, he would have lived a long life and would have built the framework of socialism among the people under the leadership of Bhagat Singh. Then he would have actually brought about a true revolution. He was not made for Lala Lajpat Rai, but to change the fate of Dalits, exploited, poor, farmers and labourers. But by going on the wrong path of nationalism, he became the destroyer of his own mission.

S.R. Darapuri I.P.S.(Retd)

National President,

All India Peoples Front

www.dalitliberation.blogspot.com

www.dalitmukti.blogspot.com

Mob 919415164845