(Kanwal Bharti)

(English translation from original Hindi: SR Darapuri, I.P.S.(Retd)

(Asian independent) The non-Vedic and materialistic ideology of India has been fundamentally egalitarian. Chandrika Prasad Jigyasu has called this the fundamental socialism of India. We find the concept of this fundamental socialism in ‘Begumpur City’ which is a much-discussed verse of Raidas Saheb –

बेगमपुरा सहर को नाउ, दुखु-अंदोहु नहीं तिहि ठाउ

ना तसवीस खिराजु न मालु, खउफुन खता न तरसु जुवालु

अब मोहि खूब बतन गह पाई, ऊहां खैरि सदा मेरे भाई

काइमु-दाइमु सदा पातिसाही, दोम न सोम एक सो आही

आबादानु सदा मसहूर, ऊहाँ गनी बसहि मामूर

तिउ तिउ सैल करहिजिउ भावै, महरम महल न को अटकावै

कह ‘रविदास’ खलास चमारा, जो हम सहरी सु मीतु हमारा।

The regal realm with the sorrowless name

they call it Begumpura, a place with no pain,

no taxes or cares, none owns property there,

no wrongdoing, worry, terror, or torture.

Oh my brother, I’ve come to take it as my own,

my distant home, where everything is right…

They do this or that, they walk where they wish,

they stroll through fabled palaces unchallenged.

Oh, says Ravidas, a tanner now set free,

those who walk beside me are my friends.

(gururavidasstemplesacramento.com/begampura.html)

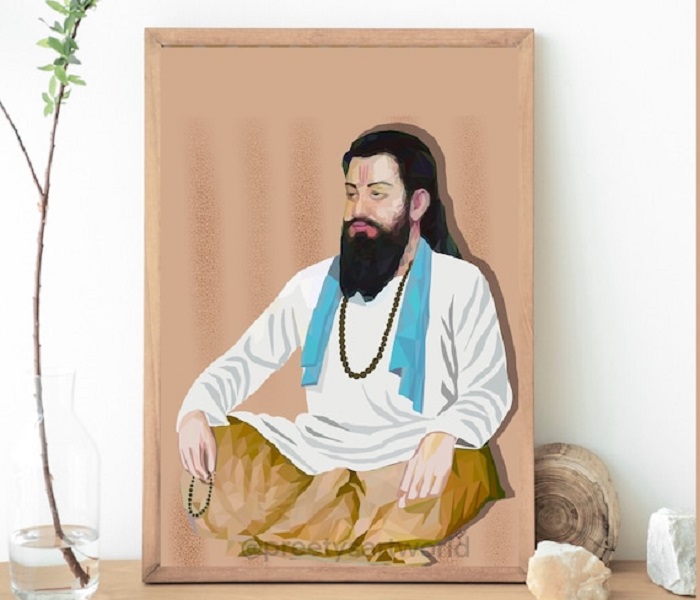

This verse is taken from ‘Amritvani Satguru Ravidas Maharaj Ji’ collected by Sant Surinder Das of Dera Sachkhand Ballan, Jalandhar. It is worth mentioning here that the real name is ‘Raidas’, not ‘Ravidas’. This change of name happened during compilation in Guru Granth Sahib. Jigyasu ji has written in this regard, ‘It could not be ascertained through whom the 40 verses of Sant Raidas ji found in Guru Granth Sahib reached and who changed Raidas to Ravidas in them? This matter is worth considering because changing ‘Raidas’ to ‘Ravidas’ is the Brahminization of Sant Pravar Raidas ji, which is the promotion of Surya-worship among Raidas-devotees.’ In other collections, this verse of Raidas Sahab is found with some changes in the text, and only ‘Raidas’ is printed on it. In Jigyasu ji’s collection, this line comes at the beginning of this verse – ‘Ab hum khub watan ghar paaya, ooncha khair sada man bhaaya.’

In this verse, Raidas Sahab has imagined a sorrow-free society while seeking freedom from the system of his time, and that is called Begumpura or Begumpur city. By this verse Raidas Saheb wants to tell that his ideal country is Begumpur, where there is no difference of high and low, rich and poor and untouchability; where no tax has to be paid, where no one is the owner of any property; there is no injustice, no worry, no terror and no torture. Raidas Saheb tells his disciples, O my brothers, I have found such a home, that is, I have found that system, which although is still far away, but everything in it is just. There is no second or third class citizen in it, rather everyone is equal. That country is always inhabited. There people go wherever they want, do whatever work (business) they want, there is no restriction on them based on caste, religion or colour. In that country the palaces (feudal lords) do not hinder the development of anyone. Raidas Chamar says that whoever supports our idea of Begumpur, he is our friend. ‘Begumpur’ can be compared to Sir Thomas More’s (1478-1535) important work ‘Utopia’, which is based on communist utopian thinking. This work, while renewing Plato’s tradition, itself became a source of inspiration in the creation of communist utopian worlds after the sixteenth century. ‘Utopia’ is an imaginary island, which is described by a Portuguese traveller Raphael Hitlode as the main character. He criticizes the systemic flaws of the feudal society prevalent in England and Western Europe and praises the ideal communist system of the island of Utopia.’

Sir Thomas More’s Utopia became so popular that from that time onwards it became a norm for an ideal imagination all over the world. More’s conclusion was that all governments are a conspiracy of the rich, which work for the rich in the name of public interest. Utopia, based on imaginary socialism, was written in two parts. But Raidas Saheb’s ‘Begumpur’ is a poem of just a few lines, in which the residents of Begumpur are as free from sorrow as the residents of the island of Utopia. If Utopia was written in reaction to the feudal system of England, then ‘Begumpur’ is a poem born out of opposition to the cruel state system and Brahminical social system of the Sultanate period. There is neither any worry nor any panic in Begumpur.

This shows how many worries the common people had during the rule of the Sultan, and fear always remained – one does not know when someone will be caught for what crime. No kind of tax has to be paid in Begumpur. But, in the kingdom of the Sultan, tax had to be paid. The biggest tax was Jaziya, which had to be paid by non-Muslims. F. E. Key has written that the fear of Jaziya tax was so great on non-Muslims, especially poor and less educated Hindus, that they could not avoid the temptation of becoming Muslims to avoid it. And many poor Hindus had achieved a good status by becoming Muslims to avoid Jaziya. There is no property owner in Begumpur and neither is there any second- or third-class citizen, all are of equal status. Many landlords, jagirdars and landowners existed during the Sultanate period. There, Muslims were considered superior, Hindus inferior and Dalit-Shudras were considered third class citizens. Begumpur is always populated by intelligent people, and the people there are living happily fulfilling their basic needs. This indicates the poverty and scarcity of the people of the Sultanate period, where even after working hard, the common people were not able to fulfil their basic needs. The residents of Begumpur are free, they can roam anywhere, there is no restriction of the (royal) palace on them. Obviously, this indicates the restrictions of untouchability, due to which the entry of Dalit castes in many places, wells, ponds and inns of Hindus was prohibited even in the Sultanate period.

Thus, these are the conclusions of the city of Begumpur – (1) Owning property is bad, (2) Paying any tax is bad, (3) Being a second-class citizen is bad, (4) Wealth and poverty are bad, and (5) Untouchability is bad. We cannot see these conclusions from the point of view of Marx’s socialist philosophy, although opposition to personal ownership of property is in accordance with it, however, from the point of view of an egalitarian society, Begumpur city was a vision ahead of its time. It was also revolutionary from the point of view of Dalit thinking of that time. This shows that Raidas Saheb was not just a poet, but also a social thinker, and an economist was also active in him. It is worth considering that the vision of Begumpur city is not found in any Hindu saint poet of the Bhakti period. There are two main reasons for this, one, they considered wealth and poverty to be the result of the karma of previous birth, and two, they were not poor. Brahmins were revered everywhere and received huge properties in donations. Kshatriyas were landowners, and Vaishyas were traders, so all of them were owners of personal property. This personal property was the reason for the prosperity of some people and poverty of many people. Poverty is a multidimensional concept, which can include social, economic and political elements. Absolute poverty, extreme poverty, or deprivation means being completely deprived of the means necessary to fulfil basic needs like food, clothing and shelter. People of Shudra-Atishudra castes were not able to fulfil their basic needs even by working hard. Thus, the caste system had created extreme prosperity on one hand, and extreme poverty on the other, which has been very vividly described by Kabir that on one side the street was paved, and on the other side there were beds and pearl necklaces. Elephants were tied at the doors of the rich. This is the same description as St. Basil had written about the rich people who indulge in pleasures that ‘They keep high breed horses decorated like grooms, but do not give clothes to their poor brothers to wear. They have many cooks, confectioners, servants, hunters, sculptors, painters and people who provide them every kind of happiness. They are the owners of herds of camels, oxen, sheep and pigs. They decorate the walls with flowers, but let the poor fellows remain naked.’

The poverty of the untouchable castes in the fifteenth century can be estimated from the autobiographies of Dalit writers published in the twentieth century, which contain a poignant description of their poor life after independence. In comparison to that, one can easily understand how painful the life of Dalit castes must have been five centuries ago. Raidas belonged to the Chamar caste, his family used to lift dead animals around Banaras. It is natural for Raidas, born in such a family, to be poor. Raidas himself has written that his condition was such that people used to laugh at his poverty. Dr. Ambedkar says that being poor is not as bad as being an untouchable. A poor person can be proud, but not an untouchable. A poor person can rise up, but not an untouchable. Raidas was poor as well as an untouchable, hence also lowly. Poverty had reached the level of destitution. There was only one piece of cloth which would tear after washing. The more they stitched it, the more it would tear again. They did not have the capacity to make a new one. But an untouchable person has to suffer not only poverty but social humiliation, which is painful. The touch of an untouchable is not limited to a few people, but it affects the whole world. Whatever an untouchable touches becomes impure. The deities in the temple become impure by his touch, the roads become impure. Food and water become impure by his touch. Even the holy water of the Ganges becomes impure. Brahmins refused to drink Ganges water in the vessels of lower castes. For them, being born in an untouchable family was a crime. A crime which was not forgiven anywhere. As soon as a person was born in an untouchable family, the restrictions of untouchability were imposed on him.

Dr. Ambedkar has called it the Hindu code, violation of which was a crime. Dr. Ambedkar has mentioned fifteen rules of the Hindu Code, whose violation was considered a crime. The main ones among them are, (1) Living separately from the population of upper caste Hindus, (2) Building a house in the south, (3) Not allowing one’s shadow to fall on an upper caste Hindu, (4) Not acquiring property in the form of money, land or animals, (5) Not putting a roof on the house, (6) Not wearing clean clothes, shoes, watches and gold jewellery, (7) Not giving names denoting high status to children, (8) Not sitting on a chair in front of an upper caste Hindu, (9) Not passing by on a horse or palanquin, and (10) Not taking out a procession or a wedding procession. On violating these rules, the entire colony of untouchables was punished. And forced labour was the destiny of the untouchables, which PremChand has shown very well in his story ‘Sadgati’. Any upper caste person would catch an untouchable for forced labour, and after making him work, would not even pay him his wages. Raidas says that this forced labour was so dreadful that even if a cobbler did not know how to mend shoes, people would force him to mend them.

In the time of Raidas Saheb, there were two centres of power. One centre was of the royal power and the other was of the power of religion. There were also two centres of religious power, the centre of power of Hindu religion was in the hands of Brahmins, while the centre of power of Islam was in the hands of Qazi-Mullah. Both these centres had interference in the royal power. The royal power did not interfere in the religious and social matters of both. Both Brahmins and Mullahs considered poverty and wealth as divine arrangements. According to Hinduism, wealth and poverty are the result of the deeds of the previous life. It calls the world false and God true and calls the worldly sorrows an illusion. Believing in this, even today the poor people are content with whatever they get and thank God. Islam also does not consider this world, that is, worldly life, as real life. According to it, the hereafter is the real life. It calls the struggle against the present sorrows and deprivations as ‘spoilage’, which Allah dislikes. In the Quran, Allah says, ‘Whatever Allah has given you, use it to build a house in the ‘afterlife’ (hereafter). Do not create spoilage on earth. Allah does not like those who create spoilage.’ Here spoilage means class-struggle. In this way, the caste system of Hinduism prevents caste-struggle, and Islam prevents class-struggle. In this way, both these religious powers are opposed to socialism. However, Islam is so brotherly that there is no untouchability, and rich and poor stand together in the mosque. Islam orders to treat the poor, orphans and the weak well. But Hinduism did not have this generosity. Therefore, in order to get respect and equality, innumerable people from untouchable castes converted to Islam. To stop this conversion, the Brahmins started the Bhakti movement in the medieval period, whose aim was to stop the Shudras from converting to Islam by making them Vaishnavs on paper. But neither this kind of conversion to Vaishnavism nor the equality of the mosque, which vanished as soon as one left the mosque, could end poverty and misery. There was no change in the social and economic condition of the Shudra castes either. It remained the same. When the leaders of the Bhakti movement used to say that ‘one who worships everyone becomes everyone’s’, they ignored the reality of discrimination among them between the rich and the poor, the touchable and the untouchable.

It was also a misconception that they said that God has created everyone equal, because in the society, along with the rich and the poor, there were low and high people, between whom there was no equality. In the world created by God, there were also exploiters, who pretended to be religious and were respected by both the religious and political authorities. In such circumstances, there was no hearing of the atrocities of the exploiters on the weak and untouchable castes. There was slavery, and slaves were bought and sold. According to ‘Tarikh Ferozshahi’, in the era of Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526), there were markets for buying and selling slaves all over the country, whose price was also fixed by Khilji. The condition of the farmers was unspeakable, it could not be described even in words. They used to take forced labour from the farmers, abuse them and torture them by locking them in dark rooms. Kabir Sahab has described a village in which the Thakur measures the field incorrectly, the village kaith (patwari) does not keep the accounts, and both together beat up the farmer. The Diwan does not listen, and Balahar ties him up and takes him away. Due to fear of them, the farmers have fled from the village.

The resistance to these above-mentioned powers is expressed in the background of Raidas sahib’s ‘Begampura’. Therefore, Raidas Sahab’s ‘Begampura’ poem, in comparison to his Nirgunvadi verses, is not a creation of spiritual experience, rather it makes us witness the feudal system of the society of that time. The dialogue style of ‘Utopia’ creates a difficulty as to how far the thoughts of the main character Raphael should be considered as the thoughts of Thomas More, but this problem does not exist with ‘Begampura’. The thoughts expressed in it are directly related to the thoughts of Raidas, in which he was laying the foundation of a system which is of socialism. It is a wonderful coincidence that both More and Raidas were contemporaries. Mor died in 1535 and Raidas in 1520. And both of them had imagined an idealistic socialism for the first time in the history of socialist thinking.

In ‘Begumpura’ Raidas Saheb says at the end, ‘Jo hum sahari su meetu hamara’(Whosoever lives in our city is our friend.) This is a very sweet statement and gives a message that goes a long way. Certainly, it would not have been possible for the Shudra-Atishudra classes to stage an organised rebellion in the fifteenth century. But in Nirgunavad, which was the philosophy of an egalitarian society, the seeds of an organised rebellion against the feudal system had already been sown. The emergence of an armed organisation called Satnami in the seventeenth century on the concept of Begumpura was the blossoming of those seeds. In Punjab, the followers of Raidas had established a political party ‘Begumpura Lok Party’ in the year 2012 based on ‘Begumpura’ and had fielded six of their candidates in the elections. It would not be wrong to say that it was Raidas Saheb’s socialist vision of ‘Begampura’ that overwhelmed Dr. Ambedkar and he accepted him as his guru.