Adivasi Day or Nag Panchami: Who Celebrates What?

(THE ASIAN INDEPENDENT UK)- Early in the morning, after getting out of bed, I often pick up my mobile phone. While checking my missed calls and messages, I noticed two messages in the form of images. The first was sent by a friend from JNU, who hails from Purnia in Bihar, and the second was from my maternal uncle.

My friend is an Adivasi and belongs to the Oraon community, which is spread across Jharkhand, West Bengal, Bihar, Nepal, Bangladesh, and other parts of the world. He wished me a happy “International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples,” celebrated globally on August 9, 2024.

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), August 9 was designated as the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples by the UN General Assembly in December 1994. It is popularly called Adivasi Divas in India, a day marked by various educational, cultural, and social functions.

My friend’s message included an image with lines written in Hindi. The text read, “Adivasi is not only a community but also a symbol of our ancestors and culture. Let’s understand, learn about it, and protect it.” The message ended with “Greetings on the occasion of the World’s Indigenous Day.” The image depicted two Adivasi women wearing caps made of leaves on their heads. They were looking at each other, smiling, and seemed to be greeting one another. I must say, it was a very beautiful way to convey the importance of Adivasi Divas.

The purpose behind holding Adivasi Day functions is “to raise awareness of the needs of” the Adivasi population, which has been the worst victim of colonialism, internal colonialism, industrialization, modernization, climate change, ecological crises, nation-building, and top-down developmental models across the world.

In India, too, the massive looting of resources in Adivasi areas was carried out by colonial masters, backed by their upper-caste native agents. While the process of colonialism ended with freedom on August 15, 1947, the process of colonization has not stopped in the post-colonial period.

A few seconds later, I received another greeting message from my maternal uncle, who lives in a village in the Muzaffarpur district of Bihar. My maternal uncle sent me a greeting card for the Nag Panchami festival.

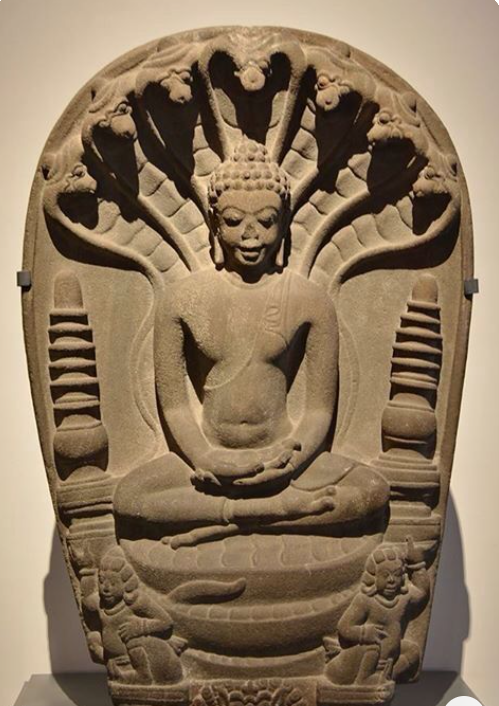

Note that “nag” is derived from the Sanskrit word “naga,” meaning snake. “Panchami” refers to the fifth day of the bright lunar month of Sawan, which falls around mid-August. On this day, Hindu devotees visit temples and worship snake idols.

Note that “nag” is derived from the Sanskrit word “naga,” meaning snake. “Panchami” refers to the fifth day of the bright lunar month of Sawan, which falls around mid-August. On this day, Hindu devotees visit temples and worship snake idols.

My maternal uncle is a Brahmin. In our locality, it is a big festival. A fair is held at temples, and children eagerly attend it. The snake-charmer communities, who are exploited and discriminated against by caste Hindus, rush to the temples and fairs to display their snakes, hoping to earn some money.

There are some myths and superstitions among caste Hindus that if milk is offered to snakes and they are worshipped on this day, the worshippers will be safe from the wrath of venomous snakes. Cases of snake bites suddenly increase during the summer and rainy seasons in Bihar due to excessive heat, rain, and flooding, and many people die due to a lack of medical facilities. Against this background, the importance of Nag Panchami can be understood.

The greeting image from my maternal uncle featured a black cobra in an agitated mood. The snake was seen raising its upper body, and its hood looked scary to most of us. Along with “Greetings of Nag Panchami,” my uncle’s message read, “May you and your family remain blessed by the snake god (nag devta).”

The reason I have shared these two different stories with you is to highlight how we, as human beings, are socially and culturally constructed. How our festivals and celebrations are deeply influenced by our own interests. How we often show our indifference and ignorance to the bigger issues. How we do not want to hear the pain of others and how the caste interests of our own become the national interests.

Let me state clearly that I am not against anyone celebrating any festival or worshipping any entity. Even India’s Constitution gives every person the fundamental right to profess any religion and faith. Similarly, my maternal uncle has every right to worship on Nag Panchami and greet me and others on this occasion. I also wish him a happy Nag Panchami.

But my question is a bit different. It is trying to question our common sense. The above-mentioned experiences have made me realize once again how our priorities and issues are deeply determined by our cultural location. Education and other factors do not change our attitudes. I have noticed that even professors who come from privileged castes have opposed reservations and justified the looting of the land in Adivasi areas.

Let me cite two recent examples to elaborate on my point. Last year, I visited the interior areas of Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh, where Adivasi communities live. For instance, in August last year, I participated in a function on the India-Nepal border in the Bahraich district of Uttar Pradesh. The area is inhabited by the Tharu Adivasi community, which is also found in Bihar and Nepal. They live in some of the most backward regions of the country, where there are no roads, no medical facilities, and not even a mobile signal. We were told that there was one school in the area, but it lacked basic facilities. The villagers have to take several buses to reach Lucknow.

Their lives are so tough that I cannot fully express them. Yet, I found them aware of Adivasi Divas. With my own eyes, I saw their social and cultural gathering. When the function was over, they ensured that visitors had food before they departed. Similarly, in the most backward regions of the Santhal belt in Jharkhand, I found Adivasi women dancing and singing on the occasion of Adivasi Divas. How could they be aware of the importance of Adivasi Divas, yet the learned high-caste professors of North India remain ignorant and indifferent towards this world festival?

Unlike the backward Adivasi belt, the more advanced regions of the north, known as the Hindi belt, hardly hold functions for Adivasi Divas. There might be a few functions here and there for World Indigenous Day, and there may be some token celebrations at educational institutes, but caste Hindus mostly prefer to remain ignorant of it. The politics of deliberate ignorance cannot be ruled out in this case.

Sadly, issues related to the most deprived communities and the protection of their resources—issues directly linked to our survival—are so often overlooked. This shows how caste society has turned its back on broader issues and is hesitant to look beyond its narrow cultural outlook. They want to colour the whole country in their own narrative outlook. They want the whole country to celebrate their own festivals as national festivals, yet they do not want to be sensitized about other cultures.

To this day, caste Hindus, who dominate universities, colleges, and the media, have never regarded Adivasi issues as national issues. Upper-caste-led politicians are often willing to send troops to Adivasi areas to “maintain law and order,” yet they fail to allocate funds to open schools, colleges, or hospitals in Adivasi villages. This shows that citizens may have equal rights on paper, but the partisan state treats them as privileged and unprivileged social groups. Similarly, the devastation of Adivasi areas is not an ecological concern for the state.

The history of post-colonial India has been written with a narrative of growth and the emergence of India as a major power and a successful democracy outside the Western world. However, much research is needed to reveal to the world the heavy price Adivasi communities have been forced to pay. While their lands were seized in the name of national development and dam construction, the fruits of this development were monopolized by outsiders, mostly caste Hindus, whom the Adivasi community dislikes and calls Dikku.

As I write this, trees are being cut down by outside agents in Adivasi areas and taken to the mainland, while poor Adivasis are not allowed to graze their cattle in the forest or pick up fallen leaves on the pretext of protecting the environment and preventing possible encroachment on government land. Yet, they do not figure in our public debate or prick the national conscience. This links to my broader hypothesis that what we think and what we celebrate is largely shaped by our caste-location and material and cultural privileges.

Dr Abhay Kumar is an independent journalist. Contact: [email protected]