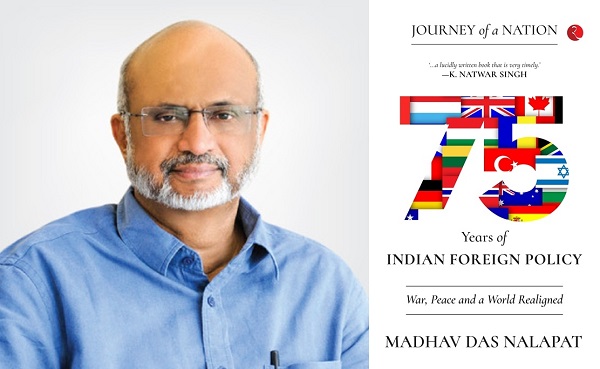

New Delhi, (Asian independent) India needs to come out of the “silos” of the “Lutyens Zone”, reverse its penchant for adopting the “soft option” on a plethora of issues and align itself with the changes in the “policymaking matrices” in countries like the US, Russia and China to ensure that the benefits of the rapid economic growth of the past few years are not “cast away”, says noted academic and strategic analyst Madhav Das Nalapat in his visionary new book, “75 Years of Indian Foreign Policy”.

The book, published by Rupa under the broad title “Journey of a Nation”, also warns against “feeding the fringe” as this “seldom makes for good politics, as this group is impossible to satisfy unless one completely surrenders to their demands at the expense of the rest of society”.

“The policymaking matrices in the US, Russia, Australia, Japan and even China have changed. The same needs to happen in India. These changes need to be comprehensive rather than, as has been the tradition in the Lutyens Zone, segmented into silos, with action by one leading to a dilution in the effectiveness of the action taken by another,” says the book, which is sub-titled “War, Peace and World Realigned” adding that what is required are effective steps from the defence, home, commerce and finance ministries in this direction.

“The higher reaches of the government need to set a correct direction for our policymaking matrix rather than working towards all-round control,” writes Nalapat, who was appointed India’s first professor of geopolitics and subsequently the UNESCO Peace Chair by Manipal University and has previously edited The Times of India, and before that Matrubhumi.

Lamenting that those who have led India “have almost always pulled away from exploiting the consequences of a breakthrough,” Nalapat writes that the 1974 Pokhran “peaceful nuclear explosion” ought to have, “in rapid succession, been followed up my more, rather than waiting until 1998 for another PM to find the resolve to go forward with another round of tests”.

Noting that after the Pokhran tests, “there was a flurry of interest in India that, for some time, was reflected even in the growth of exports of manufacturing — a country that could make a nuclear bomb could be depended upon to make the lathe”, the author decries that even Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the Prime Minister at the time, declined to follow up on Pokhran II.

“There was a moratorium on further tests and India locked itself within most of the bounds of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons although it was not a binding document.”

“Avoiding risk and looking for the soft option has been the cause of much of the pain that India and its people have endured as a consequence of defective (or at best inadequate) policy structures. Ensuring that the country gets the worst rather than the best of both worlds has become an art form in the Lutyens Zone,” Nalapat asserts, adding that the 75th anniversary of Independence “has brought with it another opportunity for the country to propel itself forward and escape from the suboptimal achievement levels that it continues to be mired in”.

Much might be made of ‘soft power’, what is often disregarded is that “to be effective, soft power must be based on a strong foundation of ‘hard power’ — the tools which do serve as sticks and carrots in international relations, such as explicit promises of trade incentives and threats of economic sanctions or military action”, the author maintains.

India’s hard power, he writes, “has grown with an increase in its economic heft and kinetic capabilities, and it is not an accident that India’s image has grown with it. Given the interdependence of other economies with India’s in this modern reality and the impact of other countries on it, policy needs to walk on two legs — foreign and domestic. The two need to be in balance, as a lack of symmetry in objectives would lead to complications that affect national life”.

“Foreign policy must promote the objectives of domestic policy, which would include economic growth, consequently improving living standards, rather than the other way around. Domestic as well as domestic opportunities need to be identified and seized, and in this process, foreign policy plays an indispensible role,” Nalapat writes.

Unlike in the past, the geopolitical opportunity now provided to India by global events “should not be missed again. Countries need to be evaluated in practical terms and treated accordingly. A productive foreign policy that will help actualise the potential dividends for India is necessary. What may appear to be hard choices for our nation’s foreign policy now may, in actuality, be the best course of action for the future of the nation,” the author adds.

Going back into history, Nalapat points out that the rise of the UK as the pre-eminent global power of its time was not the result of a conscious strategy implemented from the top but rather, was the consequence of its ruling elite giving its citizens the freedom to think and act.

“A collection of individual actions, discoveries and conquests coalesced into the British Empire. Centralised states, such as Spain and France, during that time had no chance of matching the success of the British Empire. An increasing number of people from the lower levels of society found their way to the middle, and some even discovered pathways to the top of the food chain.

“Only that society is healthy where a middle class grows proportionately to the lower classes — a middle class from which several manage to migrate upwards in terms of income and achievement. An all of government approach is indeed the panacea,” Nalapat contends.

In India’s case, “it is not known whether every element in the government accepts that policymakers need to get over the delusion that balanced relationships should always be the goal, even when such a stance may be in opposition to the national interest”, the author asserts.

In this context, Nalapat cautions that any measure or messaging “that widens the fringe in any section of the population, shrinking the moderate middle in the process needs to be avoided and, indeed, resisted by policymakers. That is why it is important to classify certain crimes, such as killing an individual for eating the meat of certain types of the bovine population, as terrorist acts”.

“In the first place, democracies should not use the bludgeon of law to effect lifestyle changes related to diet, dress or sexual orientation,” Nalapat writes, pointing out that while some countries do ban particular types of dress, lifestyle or diet (often on pain of death), this does not seem to be “garnering the attention that India has from some members of the international community for hate crimes based on the opposition to the choices of some citizens”.

“In a smart world,” Nalapat concludes, “smart policy is needed, and citizens look to such an unprecedented situation with hope. If the chance for a generation of rapid economic growth, and the benefits this brings, is cast away, historians in India might forgive those who are in power. History will not”.